Syllabus

14. Weight related comorbidities in pregnancies, the role of the obesity epidemic

(Advanced level)

Obesity is worldwide growing epidemic, affecting, both children and adults. A double fold has been observed in the incidence in more than 70 countries since 1980s, and the number of obese people in the globe tripled since 1975. The American Medical Association (AMA) declared obesity an epidemic, and the World Health Organization (WHO) called it the greatest health challenge of the 21st century. Obesity negatively impacts both mental and physical abilities and associating with comorbidities it increases the morbidity and the mortality of other conditions, like dyslipidaemia, type 2-diabetes, coronary heart diseases, ischemic stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnoe, pulmonary diseases, and malignancies (breast, endometrium, colon). Evaluating the body shape of each patient can enable us to assess the risk of occurrence in several diseases. Mostly, the impaired organ function is the result of organ enlargement, but accumulating fat tissue, for instance in case of the heart, or around the trachea plays important role in the pathogenesis. The aim of the current presentation is to shed light the special challenges and need of obese pregnant patients.

How can we determine obesity?

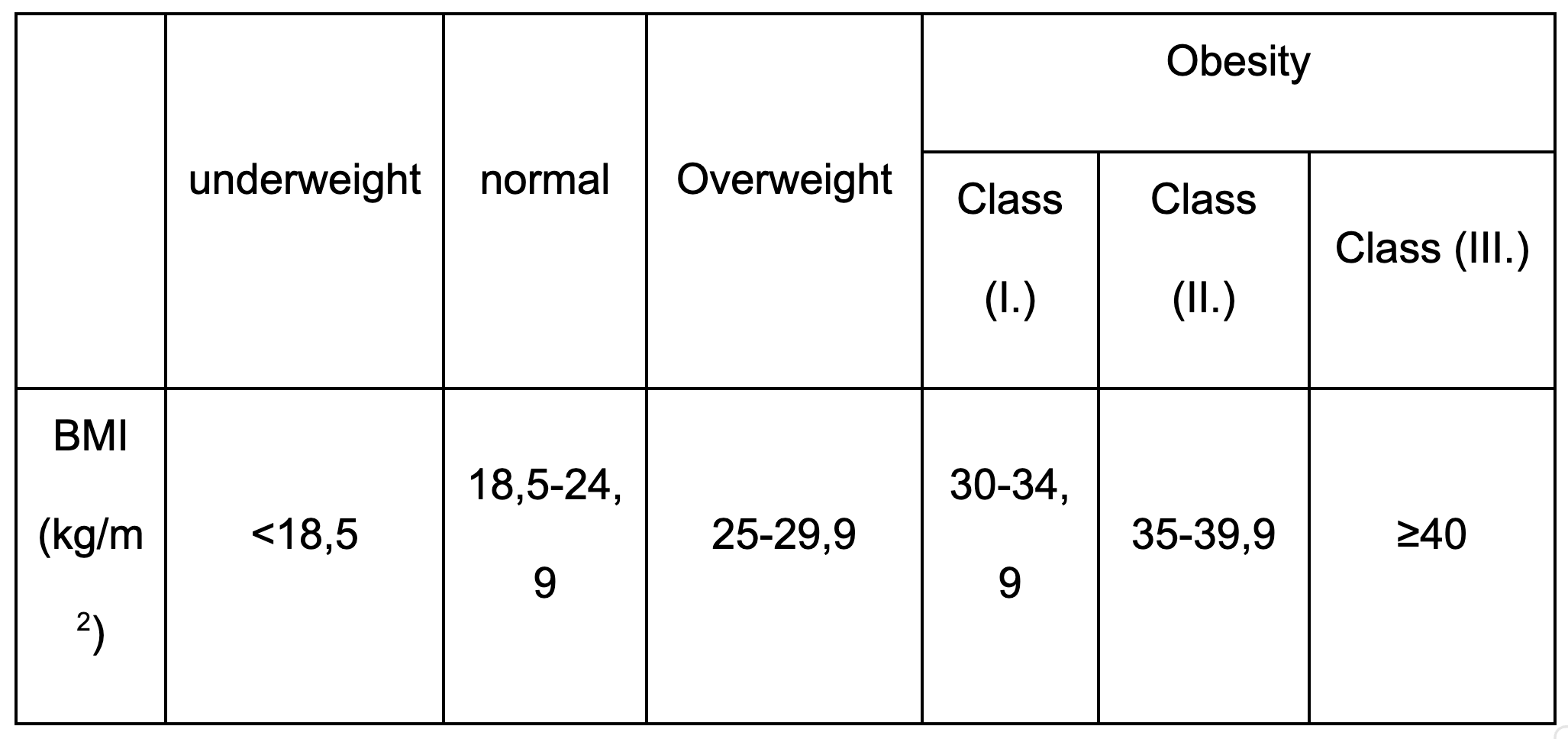

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a measure of body fat based on height and weight that applies to adult men and women. (BMI) is a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. BMI is an inexpensive and easy screening method for weight category—underweight, normal (healthy) weight, overweight, and obesity. BMI does not measure body fat directly, but BMI is moderately correlated with more direct measures of body fat. Furthermore, BMI appears to be as strongly correlated with various metabolic and disease outcome as are these more direct measures of body fatness.

What is the pathomechanism of excess weight gain?

The abundance of stored fat is required for survival during nutritionally deprived states such as starvation. In times of prolonged abundance of food, however, very efficient fat storage results in the excessive storage of fat, eventually resulting in obesity.8-10 It has been hypothesized that the storage of fatty acid as triacylglycerol within adipocytes protects against fatty acid toxicity; otherwise, free fatty acids would circulate freely in the vasculature and produce oxidative stress by disseminating throughout the body. however, the excessive storage that creates obesity eventually leads to the release of excessive fatty acids from enhanced lipolysis, which is stimulated by the enhanced sympathetic state existing in obesity. The release of these excessive free fatty acids then incites lipotoxicity, as lipids and their metabolites create oxidant stress to the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. This affects adipose as well as nonadipose tissue, accounting for its pathophysiology in many organs, such as the liver and pancreas, and in the metabolic syndrome. The free fatty acids released from excessively stored triacylglycerol deposits also inhibit lipogenesis, preventing adequate clearance of serum triacylglycerol levels that contribute to hypertriglyceridemia. Release of free fatty acids by endothelial lipoprotein lipase from increased serum triglycerides within elevated β lipoproteins causes lipotoxicity that results in insulin-receptor dysfunction. The consequent insulin-resistant state creates hyperglycemia with compensated hepatic gluconeogenesis. The latter increases hepatic glucose production, further accentuating the hyperglycemia caused by insulin resistance. Free fatty acids also decrease utilization of insulin-stimulated muscle glucose, contributing further to hyperglycemia. Lipotoxicity from excessive free fatty acids also decreases secretion of pancreatic β-cell insulin, which eventually results in β-cell exhaustion [Richard N. Redinger, MD: The Pathophysiology of Obesity and Its Clinical Manifestations].

Obesity interacts with inherited factors and leads to hyperinsulinaemia. Thismetabolic abnormality is responsible for altered glucose metabolism, and predispose to type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dyslipidaemia and hypertension. When clustered together with other insulin-resistance related subclinical abnormalities, these are referred to metabolic syndrome [William’s Obstetrics, 23rd Edition-McGrow Hill, Chapter 43]. Complications and their possible cause are demonstrated in the presentation.

What will be the consequences of maternal obesity?

Obviously, all pregnant women gain weight, since near term the fetus weights 3.5 kg, the amniotic fluid weight 1.5 kg and the placenta weights 1 kg in average, not to mention the increased plasma volume and the accumulating water in the body due to progesterone effect. What is mor important, whether the women were considered to be obese before conception or gained excess weight during the 9 months of pregnancy. The ideal weight gain during pregnancy is determined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendation, in which height and race related recommendations apply, although classification is based on BMI values.

If the mother was prepragncy obese, she should not start weight loss during the pregnancy, since catabolic state can harm the fetus, and disrupt fetal development. Although weight gain recommendations still apply for them, with extra precautions. For example, obesity is associated with increased incidence of neural-tube defects. therefore, early folic acid supply is necessary.

What kind of complications can arise during pregnancy in obese women?

Adverse pregnancy events include:

1, Early pregnancy:

-Miscarriage

-Congenital anomalies e.g. neural tube defects

2, Late pregnancy:

-Preterm labour

-Hypertension/ pre-eclampsia

-Gestational diabetes

-Thrombo-embolism

3, Labour & Delivery

-Difficulty in fetal surveillance

-Prolonged labour/ dysfunctional labour

-Increased rate of instrumental deliveries

-Increased perineal trauma

-Increased incidence of shoulder dystocia

-Increased incidence of genital and urinary tract infections

-Instrumental deliveries

-Caesarean sections

-Primary postpartum haemorrhage

-Higher risk of anaesthetic complications

4, Postpartum:

-Increased risk of perineal / caesarean wound breakdown and infection

-Postpartum endometritis

-Secondary PPH

-Postpartum thrombophlebitis / thromboembolism

-Reduced breastfeeding

5, Fetus and neonate:

-Macrosomia

-Intrauterine Growth Restriction

-Intrauterine death

-Early neonatal death

-Hypoglycaemia

-Childhood adiposity

-Meconium aspiration

-Birth trauma

-Neural tube defects

-Cardiovascular anomalies

-Ano-rectal atresia

-Hydrocephaly

-Limb reduction anomalies

-Septal anomalies

Vitamin supplements: It is recommended that obese women should take high dose (5mg) folic acid for at least one month before conception and continue throughout the first trimester as obese women are at increased risk of neural tube defects. Interpregnancy weight reduction among women with obesity has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of developing gestational diabetes (GDM). Studies found that a weight loss of at least 4.5 kg before the second pregnancy reduced the risk of developing GDM by up to 40%. Although it has been suggested that some weight loss regimens during the first trimester may increase the risk of fetal neural tube defects (NTD), weight loss prior to pregnancy does not appear to carry this risk.

Obesity and exercise

Unless there are medical or obstetric contradictions obese women should be encouraged to maintain regular exercise during and after pregnancy. Maintaining exercise during pregnancy may have many benefits including short terms benefits to

the baby and long-term benefits for the mother and further pregnancies. Physical exercise during pregnancy is associated with a decreased risk of pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus.

Risk factors.

No additional risk factors: Women with a booking BMI >35 with no additional risk factor can have community monitoring for preeclampsia at a minimum of: 3 weekly intervals between 24 and 32 weeks gestation, 2 weekly intervals from 32 weeks to delivery.

One additional risk factor: Women with a booking BMI >35 who also have at least one additional risk factor for preeclampsia should have referral early in pregnancy for specialist input to care.

Additional risk factors include:

• first pregnancy,

• previous pre-eclampsia,

• >10 years since last baby,

• >40 years, family history of pre-eclampsia,

• booking diastolic BP >80mmHg,

• booking proteinuria >1+ on more than one occasion or >0.3g/24 hours,

• multiple pregnancy,

• and certain underlying medical conditions such as antiphospholipid antibodies or pre-existing hypertension, renal disease or diabetes.

More than one additional risk factor: The NICE Clinical Guideline on Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy states that women with more than one moderate risk factor may benefit from taking 75mg to 150 mg aspirin daily from 12 weeks’ gestation until birth of the baby.

Glucose tolerance tests BMI 30 – 35 - GTT at 28 weeks is recommended if there is a first degree relative with diabetes / their family origin is South Asian, Black Caribbean or Middle Eastern.

BMI > 35 - GTT at 28 weeks and appropriate referral if gestational diabetes diagnosed.

Additional Ultrasound scans

BMI > 35 - Growth scans at 30 and 36 weeks gestation.

BMI > 40 - Growth scans at 30 and 36 weeks gestation

Thromboprophylaxis

Women with a booking BMI > 30 should be risk assessed at booking and every visit for risk of thromboembolism. The RCOG Clinical Green Top Guideline No. 37 advises that: A woman with a BMI >30 who also has two or more additional risk factors for thromboembolism should be considered for prophylactic low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) antenatally. All women receiving LMWH antenatally should usually continue prophylactic doses of LMWH until six weeks postpartum, but a postnatal risk assessment should be made.

All women with a BMI >40 should be advised to have postnatal thromboprophylaxis for at least 10 days regardless of their mode of delivery and TED stockings should be worn irrespective of mode of delivery.

Birth plan:

For women with a BMI over 30 kg/m2 at the booking appointment, carry out a risk assessment in the third trimester. When developing the birth plan with the woman, take into account:

the woman's preference

the woman's mobility

comorbidities

the woman's current or most recent weight

BMI > 40

• Women with a BMI >40 should be advised to deliver in the Delivery Suite (obstetric led).

• Correct size blood pressure cuff must be available and used.

• An assessment for the risk of thromboembolism should be performed on admission.

• The portable scanner should be used to check / confirm presentation on admission.

• In view of the importance of obtaining an adequate fetal heart trace, consideration should be

given to using a fetal scalp electrode early in labour.

• The anaesthetic middle grade should be informed of the woman’s admission.

• Adequate analgesia should be provided. If an epidural is the preferred choice of analgesia it

should be sited early.

The on call consultant anaesthetist should be informed of the woman’s admission if BMI > 50.

• Intravenous access with a large gauge cannula should be established in labour due to the increased risk of complications.

• A copy of the antenatal anaesthetic risk assessment should be available in the notes and reviewed by the duty anaesthetist on call when the woman is admitted in labour.

• Water and isotonic sports drinks only should be given in labour.

• Any additional equipment required should be available and used.

• Pressure areas should be checked two-hourly and skin integrity maintained. This

should be documented in the notes.

• Active management of the third stage of labour should be recommended because of the

increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage.

Induction of labour

Elective induction of labour at term in obese women may reduce the chance of caesarean birth without increasing the risk of adverse outcomes; the option of induction should be discussed with each woman on an individual basis.

Where macrosomia is suspected, induction of labour may be considered. Parents should have a discussion about the options of induction of labour and expectant management.

Vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC)

Women with a booking BMI >30 should have an individualized decision for VBAC following informed discussion and consideration of all relevant clinical factors.

Obesity is not a contraindication for attempting a VBAC. Obesity is however a risk factor for unsuccessful VBAC, and morbid obesity carries a greater risk for uterine rupture during trial of labour and neonatal injury. Continuous fetal monitoring is recommended. Emergency caesarean section in women with obesity is associated with an increased risk of serious maternal morbidity because anaesthetic and operative difficulties are more prevalent in these women compared to women with a

healthy BMI, and this should also be taken into account when discussing the risks and benefits of VBAC.

Postnatal Care all Women with BMI >30

• Early mobilization should be encouraged.

• Breast feeding should be encouraged. Appropriate support should be given to women postnatally regarding the benefits, initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding.

• Any wounds should be observed for signs of dehiscence and infection. The woman should be advised to keep wound dry.

• Women should be given advice on the signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

• The woman’s weight should be discussed postnatally. The benefits of a healthy diet and exercise should be discussed and the benefits to a future pregnancy of her losing her pregnancy weight gain discussed.

• LMWH All women with a BMI greater than 40 at booking, should be recommended to have at least ten days of LMWH after delivery. This should be extended to six weeks in the presence of other risk factors for venous thrombosis.

Conclusions

Excessive weight has become one of the major health problems in affluent societies. Obesity is a condition that is habitually present, and its prevalence continued to increase since the 1960s. There are many obesity-related medical conditions, together they significantly reduce the life span of an individual. Obese women who became pregnant, and their fetuses, are predisposed to variety a serious pregnancy-related complications. This also includes increased risk of maternal mortality and morbidity, moreover recent studies highlight the that the offspring of obese mother also suffer long-term morbidity.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the Foundation for the Development of the Education System. Neither the European Union nor entity providing the grant can be held responsible for them.