Learning material

Endometriosis- Cultural differences in pain expression and communication

SYLLABUS

Endometriosis- Cultural differences in pain expression and

communication

(Advanced)

Introduction

In this presentation, you will understand how humans began framing pain as a psychological, physical, and cultural phenomenon. We will take the example of endometriosis, characterised by chronic pain. Initial slides will inform about the basic characteristics of endometriosis, then we will deep dive in the current definitions of pain. Beginning with the “official,” recent definition of pain, the following slides will sum up the history of pain theories, and then we will focus on the biopsychosocial model of pain. From that point the presentation will explore the biological, psychological, and cultural domains of pain. After explaining the biopsychosicial model and highlighting aspects such as racism, or opportunities for pain expression among vulnerable people, or the manifestation of social responsibility within human rights, the importance of communication strategies within the doctor-patient relationship will be discussed.

Slide 1 – INTRODUCTION

The introduction provides a comprehensive overview of endometriosis, a chronic condition characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. This condition commonly causes significant pelvic pain and infertility. It discusses how the aberrant growth and function of this tissue are influenced by hormonal and inflammatory factors. The slide also highlights the prevalence of endometriosis, noting that it affects an estimated 10% of women of reproductive age.

Slide 2 – PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND PREVALENCE

This section delves into the pathophysiology of endometriosis. It explains various theories of its development, such as retrograde menstruation, where endometrial tissue enters the abdominal cavity through the reflux of menstrual blood, and coelomic metaplasia, where peritoneal tissue transforms into endometrial tissue. Other discussed theories include lymphovascular dissemination, where endometrial tissue spreads via the lymphatic and vascular systems, and the role of bone marrow-derived stem cells. Additionally, it covers epigenomic and genomic changes that may explain abnormal gene expression in endometriotic lesions. The slide also provides detailed prevalence data to underscore the widespread nature of this condition.

Slide 3 – SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSIS

The third slide outlines the common symptoms of endometriosis, including chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation), dyspareunia (pain during intercourse), infertility, and various gastrointestinal symptoms. It describes the diagnostic process, emphasizing the importance of a thorough clinical history and pelvic examination. The role of imaging techniques such as ultrasound and MRI is highlighted, alongside the definitive diagnosis made through laparoscopy, which allows for direct visualization and histological confirmation of endometriotic tissue.

Slide 4 – TYPES OF ENDOMETRIOSIS

This section explains the different types of endometriosis, each with distinct clinical manifestations. Superficial endometriosis involves the outermost layer of pelvic organs, while deep infiltrating endometriosis penetrates deeply into surrounding tissues, such as the bladder or bowel. Ovarian endometriomas are cysts formed on the ovaries due to endometrial tissue growth. The slide provides insights into the pathogenesis theories associated with each type, including retrograde menstruation, coelomic metaplasia, lymphovascular dissemination, bone marrow-derived stem cells, and invagination theory.

Slide 5 – MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT

The management and treatment slide focuses on various strategies to alleviate the symptoms and complications of endometriosis. Pain management is addressed through the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and hormonal therapies, such as oral contraceptives, progestins, and GnRH agonists. Surgical options, including excision of endometriotic lesions, are also discussed. For women seeking pregnancy, fertility preservation methods like assisted reproductive techniques (ART) are highlighted. The importance of a multidisciplinary approach, involving gynecologists, pain specialists, and mental health professionals, is emphasized for holistic management of the condition.

Slide 6 – COMPLICATIONS AND IMPACT

This section describes the various complications associated with endometriosis, including adhesions, ovarian cysts, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain. It also addresses the psychological distress that often accompanies the condition. The slide emphasizes the significant impact of endometriosis on quality of life, noting how it impairs physical and emotional well-being, decreases productivity, and disrupts relationships. The comprehensive nature of the condition's impact underscores the need for effective management and support.

Slide 7 – ENDOMETRIOSIS AND PAIN

Here, the course explores the mechanisms of pain in endometriosis. It discusses how inflammation, nerve infiltration, prostaglandin production, and pelvic muscle dysfunction contribute to the pain experienced by patients. The concept of central sensitization is introduced, explaining how endometriosis-associated pain can lead to an amplification of pain perception, contributing to chronic pain syndromes. This slide highlights the complex interplay between endometriosis and pain, providing a deeper understanding of the condition's debilitating effects.

Slide 8 – RESEARCH AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This slide highlights current research trends and future directions in the treatment and understanding of endometriosis. It discusses the discovery of biomarkers for early detection and personalized treatment, as well as novel therapies targeting specific pathways involved in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. The emphasis on patient-centered care is also highlighted, stressing the importance of improving patient education, advocacy, and support networks. The slide underscores the ongoing efforts to advance the diagnosis, treatment, and overall management of endometriosis through research and innovation.

Slide 9 – DEBATED TOPICS AND TAKE HOME MESSAGE

The final slide covers current debates in the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. It discusses controversial topics and differing opinions within the medical community. The slide concludes with a take-home message that emphasizes the complexity of endometriosis and its significant implications for women's health and quality of life. It highlights the necessity of multidisciplinary collaboration and ongoing research to improve the outcomes for individuals affected by this condition.

Slide 3-5: Definition of pain

According to the definition of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), “Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” (IASP, 2020). The IASP recommended six key notes as an expansion for further valuable context. These include:

“- Pain is always a personal experience that is influenced to varying degrees by biological, psychological, and social factors.

- Pain and nociception are different phenomena. Pain cannot be inferred solely from activity in sensory neurons.

- Through their life experiences, individuals learn the concept of pain.

- A person’s report of an experience as pain should be respected.

- Although pain usually serves an adaptive role, it may have adverse effects on function and social and psychological well-being.

- Verbal description is only one of several behaviors to express pain; inability to communicate does not negate the possibility that a human or a non-human animal experiences pain.”

This definition is widely accepted and underlines very important features of pain which were not obvious previously. (source: https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/iasp-news/iasp-announces-revised-definition-of-pain/)

Slide 6-8: History of pain theories

Throughout history, various pain theories have existed. The ideas that pain is not solely physical, that phantom pain exists, that cognition and emotion affect pain, and that vulnerable creatures, which cannot articulate their emotions, could also feel pain, was not obvious to humans. It took a long time for different concepts about pain, as described above, to be articulated.

Before introducing the biopsychosocial model, let's first introduce some basic theories of pain as discussed by Trachel and Cascella (2019).

The Intensity Theory of pain, originating from Plato's work Timaeus, defines pain as an emotion triggered by intense and lasting stimuli. Over centuries, our understanding has evolved, recognizing chronic pain as a dynamic experience that changes over time and space. Nineteenth-century experiments, involving tactile and electrical stimulations, aimed to establish the scientific foundation of this theory. These investigations shed light on tactile perception thresholds and the involvement of dorsal horn neurons in pain transmission and processing.

The Cartesian Dualistic Theory - Rene Descartes' Cartesian dualism theory in 1644. This theory posited that pain resulted from either physical or psychological injury, with no interaction between the two. Descartes also suggested a connection between pain and the soul, locating the soul of pain in the pineal gland and designating the brain as the moderator of painful sensations. However, this theory fails to explain various factors contributing to pain and the differences in pain experiences among chronic pain patients. Nonetheless, it laid a foundation for further scientific exploration of pain.

The Specificity Theory, initially proposed by Charles Bell in 1811, delineates different types of sensations to different pathways, similar to Descartes' dualistic approach to pain. It suggests specific pathways for sensory inputs and views the brain as a complex structure rather than a homogenous object. Over the next century and a half, scientists further developed this theory, with contributions from Johannes Muller and Maximillian von Frey. However, while significant advancements were made in understanding pain, the theory fails to consider non-physical factors contributing to pain sensation and lacks an explanation for persistent pain post-injury. This incomplete understanding has led to the need for additional theories and ongoing research.

The Gate Control Theory, proposed by Patrick David Wall and Ronald Melzack in 1965, marked the first attempt to understand pain from a mind-body perspective. This theory expanded upon previous notions and introduced the concept of a "gate" in the spinal cord that regulates pain signals to the brain. When the gate is closed, pain signals are inhibited, but when it opens, pain is experienced. This theory emphasized the interaction between physical and psychological factors in pain perception. Melzack and Wall suggested additional control mechanisms in the brain, highlighting the influence of cognitive and emotional factors on pain. Recent studies have also indicated that a negative mental state can heighten the brain's receptivity to pain signals. For instance, individuals experiencing depression may have a more frequently open "gate," allowing for increased transmission of signals, thereby elevating the likelihood of heightened pain perception even from mundane stimuli. Moreover, there are accounts suggesting that certain unhealthy lifestyle choices can similarly keep the "gate" open, resulting in exaggerated pain responses disproportionate to the stimulus. The gate control theory stands out as one of the most impactful contributions to pain research in history. The foundational concepts introduced by Melzack and Wall remain integral to contemporary research practices. Despite its recognition that pain is not solely a consequence of physical injury but a multifaceted experience influenced by cognitive and emotional factors, further research is imperative to fully grasp pain mechanisms and etiology. This necessity has spurred the emergence of subsequent philosophies concerning pain.

The Neuromatrix Model, introduced by Ronald Melzack almost thirty years after his Gate Control Theory, revolutionized the understanding of pain perception. Unlike earlier theories that attributed pain solely to physical injuries, Melzack's model emerged from observations of amputees experiencing phantom limb pain. This model proposes that the central nervous system, rather than peripheral signals alone, is responsible for generating painful sensations. Within the central nervous system, four components interact to create what Melzack termed the "neurosignature," allowing individuals to perceive pain. These components include various brain regions such as the spinal cord, brain stem, limbic system, and cortex. Importantly, the model emphasizes that while peripheral inputs can influence the neurosignature, they cannot create it independently. Additionally, Melzack highlighted the role of cognitive and emotional factors in pain perception, suggesting that stress can exacerbate pain. Despite advancing the understanding of pain's complexity, the Neuromatrix Model does not fully incorporate social constructs of pain. Thus, further research and theories are needed to comprehensively explain pain mechanisms and individual experiences.

Slide 9: Biopsychosocial model

The Biopsychosocial Model offers a comprehensive explanation for pain etiology, emphasizing the intricate interactions between biological, psychological, and sociological factors. It asserts that any theory failing to consider these factors inadequately explains pain. While the term "biopsychosocial" was coined in 1954 by Roy Grinker, the approach was utilized earlier by physicians like John Joseph Bonica, who advocated for interdisciplinary pain clinics after World War II. George Engle, in 1977, emphasized multidimensional concepts in disease management. John D. Loeser furthered this model in pain assessment, considering nociception, pain, suffering, and pain behaviors. These elements collectively account for an individual's pain experience. The Biopsychosocial Model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and managing chronic pain effectively.

Slide 10-12: Biological domain of pain

If we aim to effectively treat, we must focus on three interconnected domains of equal importance: biology, psychology, and social functioning. The biological aspect encompasses genetics, hormones, tissue damage, inflammation, anatomical issues, system dysfunction, as well as sleep and nutrition. Although this domain usually receives the most attention, it only accounts for one-third of the model. The remaining two-thirds involve psychosocial factors, which are crucial to address for successful treatment but are often overlooked. (Zoffness 2019)

Understanding the biological components of pain is also essential for comprehending its neuropsychology. Activity in both the peripheral and central nervous systems influences the experience of pain. (Jensen 2011)

Peripheral mechanism:

•Tissues outside the brain and spinal cord have receptors for physical injury.

•These receptors are categorized by nerve fiber types.

•Activation of these receptors and transmission of information along nerve fibers isn't pain.

•Pain results from specific brain structures being activated.

•Information signaling physical damage is called nociception; receptors for this are nociceptors.

•Nociceptors vary in sensitivity and respond differently to stimuli.

•Factors influence mechanical and chemical changes affecting nociceptor sensitivity.

Spinal Mechanisms

•Nerve fibers carrying pain signals from the body enter the spine at the dorsal horn.

•These fibers connect with nerves that send information up the spine to the brain.

•Most spinal nerves relay information to the thalamus, a key brain relay station.

•This information highway, known as the spinothalamic tract (STT), transmits pain signals to the brain.

•The responsiveness of STT neurons to pain is influenced by signals from the brain to the spinal cord.

•The brain can reduce STT cell sensitivity to pain.

•Research shows that stimulating the midbrain's periaqueductal gray (PAG) area results in pain relief.

•The PAG receives input from brain areas involved in pain processing, indicating our brains can inhibit pain signals from the body.

Supraspinal Mechanisms - Pain is perceived when complex integrated cortical (supraspinal) systems are engaged.

•Thalamus: it is the brain’s primary relay center, transmitting sensory information from the periphery and spinal cord to various sites in the cortex

•Somatosensory cortex: encodes spatial information about nociception (that is, they help to tell us where on the body damage has or might have occurred), and involved in encoding the severity and quality of the stimulus/ nociception.

•Anterior cingulate cortex: art of the limbic system, plays a role in various processes and activities. Evidence links ACC activity to the emotional aspect of pain. It's also involved in preparing for pain management, aiding cognitive, behavioral, and emotional coping efforts.

• Insula: A limbic system component primarily responsible for sensory processing, encoding a person's physical condition related to motivation (e.g., hunger, pain). When the brain detects discrepancies between survival needs (e.g., oxygen) and perceived conditions (e.g., low blood sugar), the insula triggers alarm signals."

•Prefrontal cortex: Involved in complex cognitive responses, social behavior, and executive functions. Concerning pain, it encodes cognitive aspects like pain memory, evaluation, and executive decisions. Decisions regarding pain management are translated into coping behavior with assistance from the ACC and motor cortex.

Slide 11-12: Psychological domain of pain

- The psychological domain of pain includes thoughts and beliefs, coping behaviours, prior experiences and expectations, and emotions.

- Thoughts and beliefs: Pain-related fear is often more debilitating than the pain itself, as it leads to avoidance behaviors that affect daily activities and contribute to the transition from acute to chronic pain. Fear of further injury can hinder recovery. Additionally, beliefs about one's ability to manage pain (pain self-efficacy) are crucial in determining pain behaviors and associated disability. Recent research suggests that self-efficacy beliefs play a more significant role in disability than fear avoidance beliefs among patients with musculoskeletal pain. Pain self-efficacy mediates the relationship between pain severity, fear, and disability, as well as between pain intensity and depression. Internal pain control mechanisms can also help reduce depression and pain behavior following treatment. (Baird and Sheffield 2016) (see later)

- Coping behavoiurs: In general, coping mechanisms can be divided into two categories: active coping and passive coping. Active coping involves the patient's efforts to manage pain using internal resources to exert control over it. On the other hand, passive coping, typically involves avoiding activity and feeling helpless to address the pain, often relying on external resources for control. Passive coping may result in physical inactivity, which can lead to physical decline. Additionally, coping strategies for pain can be further classified into cognitive methods, like distraction, and behavioral approaches, such as taking pain medication. (Prell et. al 2021)

- prior experiences and expectations:

- Emotions: Attentional and emotional factors have been identified as influencers of pain perception, both in clinical settings and laboratory environments. However, the manner and mechanisms through which they exert this influence vary. While focusing on pain tends to heighten the perceived intensity of the sensation, experiencing negative emotions tends to amplify the perceived unpleasantness of pain, albeit without altering its intensity. For instance, one study revealed that emotional valence affected pain ratings and spinal nociceptive reflexes similarly, but distraction reduced pain while enhancing the reflex. This suggests that distinct systems might be engaged in the modulation of pain by attention and emotions. (Bushnell et. al 2013)

Overall, the pain pathway is bidirectional: pain affects emotions and cognition, while they also influence pain. The figure Bushnell et al. illustrates this relationship: „Pain can have a negative effect on emotions and on cognitive function. Conversely, a negative emotional state can lead to increased pain, whereas a positive state can reduce pain. Similarly, cognitive states such as attention and memory can either increase or decrease pain. Of course, emotions and cognition can also reciprocally interact. The minus sign refers to a negative effect and the plus sign refers to a positive effect.” (Bushnell et al, 2013)

Slide 13-17: Social domain

The social aspects of pain are multifaceted. Among them, we highlight only a few - as an example: gender relevance, race, ethnicity, racism, vulnerable groups, and the question of social responsibility.

Slide 14: Gender pain gap

The concept of the 'gender pain gap' refers to both biological and psychosocial differences in pain perception between males and females. This phenomenon gained such significance that in 2008, the International Assotiation for the Study of Pain (IASP) organized a 'Real Women, Real Pain' campaign to highlight its importance and necessity.:

“Every day millions of women around the world suffer from chronic pain but many remain untreated. Several reasons may explain why barriers to treatment still exist. Psychosocial factors, such as gender roles, pain coping strategies and mood may influence how pain is perceived and communicated. In addition, there may be a lack of acceptance or understanding of the biological differences between men and women that may impact how pain is perceived. These psychosocial and biological factors, coupled with the economic and political barriers that still exist in many countries, have left millions of women living in pain without proper treatment.” (IASP)

Their program aimed to educate various stakeholders, including the public, healthcare providers, and government leaders, about the lack of diagnosis and adequate treatment of chronic pain in women. (IASP 2007)

Slide 15: Race, etnicity, racism

Certainly:

Misconceptions about biological differences between blacks and whites among white laypeople, medical students, and residents lead to racial biases in pain perception and treatment recommendations, contributing to disparities in pain assessment and treatment. (Hoffman et. al 2016)

It is rare for individuals who are not in positions of power and are not taken seriously due to prejudices to speak in detail about discrimination, although there are increasingly more programs and research aiding in uncovering bias. For instance, Mara Oláh, also known as Omara, a Hungarian Romani painter, described her decades-long struggles with pain as follows:

“At the age of 13, when my first menstruation arrived, a year later I was already tormented by such crampy pains that I was on the verge of unbearable. And what to do in such cases? You turn to a doctor. Begging, pleading with dear Doctor Sir, alleviate my pain, because I'm going crazy! And what was the response, you might wonder? Well, the dear gynecologist doctor promptly ushered me out of the office with the statement:

- There's nothing wrong with you, every woman has menstrual cramps like this, only you gypsies can't bear the pain because you lack willpower!

-Get out of my office, and I don't want to see you again! Because gypsies are all like this, always throwing a tantrum!

So how did my ordeal, which lasted for ten years, continue? So it turns out the gypsy wasn't throwing a tantrum after all, but was actually sick.” (Oláh 1997: 28)

The significance of this story lies in the fact that a Romani woman was able to voice the injustice done to her, serving as an example to other Romani women to raise their voices against discrimination they face (OFF Biennalé, 2021). However, despite this, in Hungary today - as participatory theater performances, for example, demonstrate - the situation of Roma women in gynecological practices has not improved much.

Slide 16: Vulnerable Groups

As seen in the IASP’s keynote, supplementing our definition (sliede 3), IASP emphasized the importance of highlighting that verbal description is only one way to express pain; the inability to communicate verbally does not negate the possibility of experiencing pain for both humans and non-human animals. The fact that we even accept the possibility of pain in those unable to verbally express it was far from evident. This is well illustrated by the fact that, although infant pain was recognized in ancient history and even in the 17th century, the reliance on scientific methodology and prevailing scientific theories in the late 19th and 20th centuries led to almost universal denial of pain perception in infants. For example, conclusions were drawn suggesting that children were less evolved beings. The issue of pediatric pain only came into focus in the 1981-1990 period. (Anand et. al 2020)

Today, particular attention is paid to groups who are unable to verbally express pain when developing and using tools suitable for pain expression.

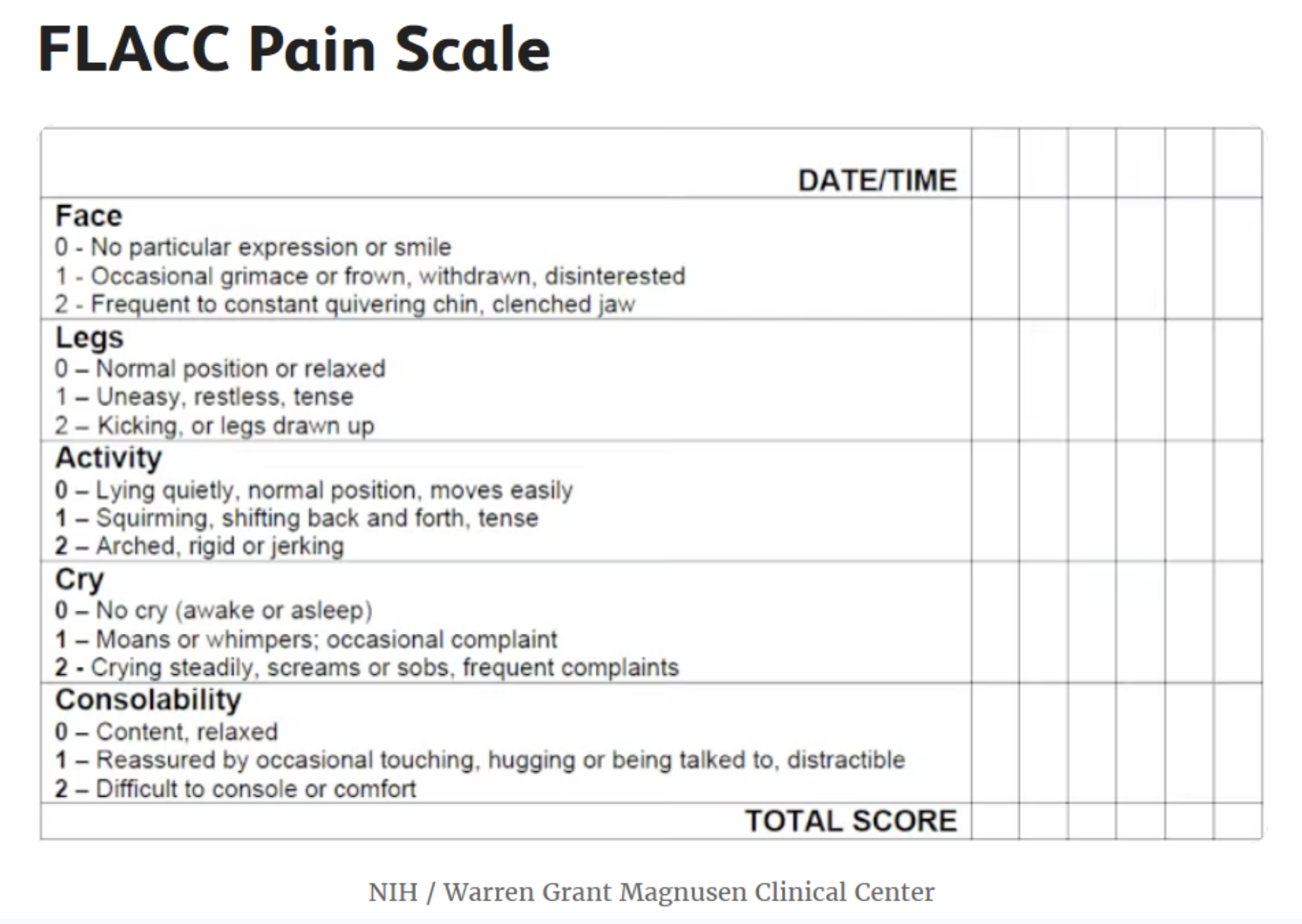

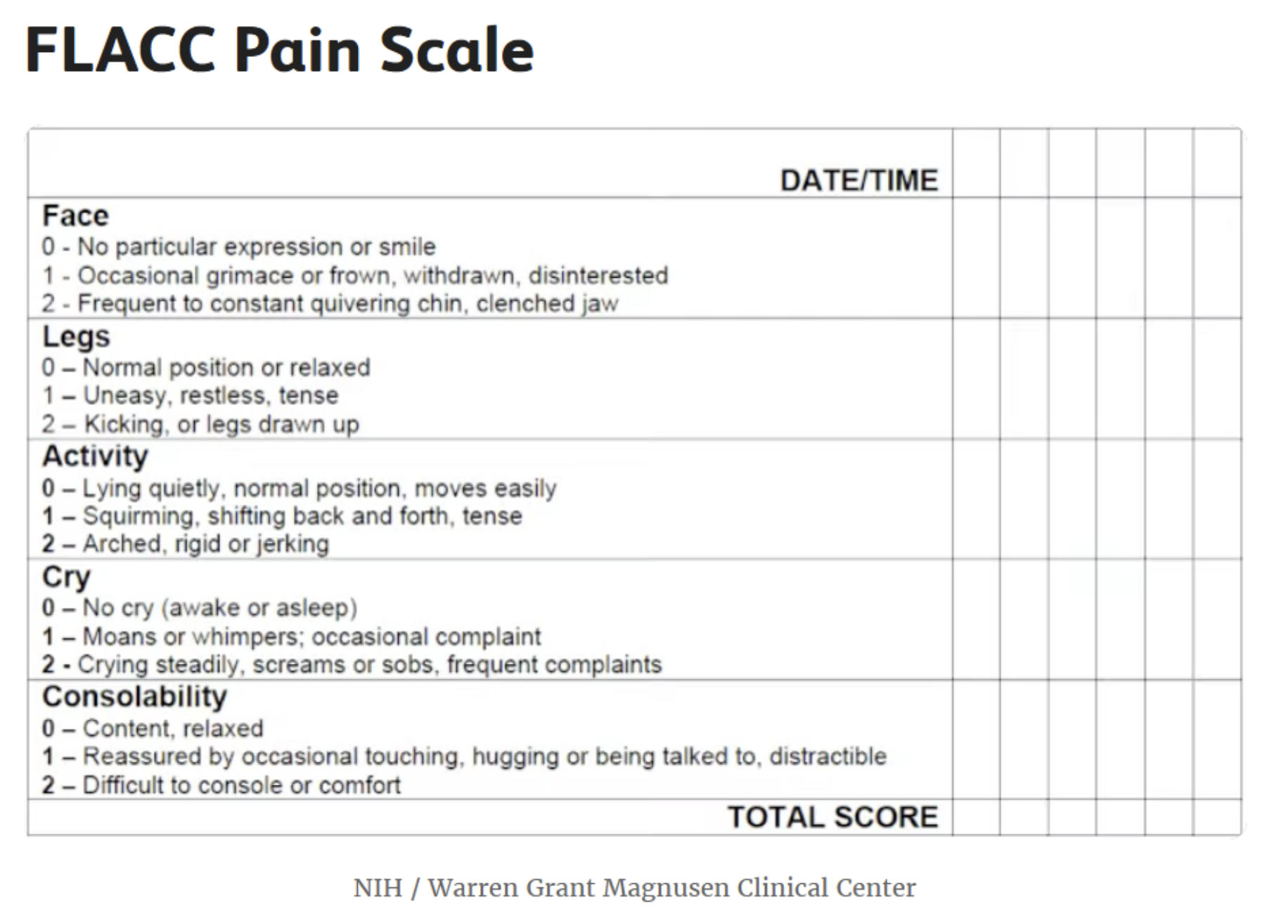

There are also scales that help doctors understand patients who may not even have the opportunity to express their pain through pictures. The The FLACC Pain Scale, for example, is a method used to assess pain in infants and young children. The abbreviation FLACC stands for the following:

F - Face: Expression of the face, including the eyes, nose, and mouth.

L - Legs: Movement or restlessness of the legs.

A - Activity: Restlessness or calmness of the child.

C - Cry: Nature of the child's crying.

C - Consolability: How easily the child can be comforted.

Each part of the scale is scored from 0 to 2, and based on the total score, the severity of the child's pain can be assessed. This method can help healthcare professionals provide appropriate treatment for children for pain relief.

Slide 17: Social Responsibility – Human Rights

Pain management is considered a fundamental human right in the context of community solidarity. The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the United Nations Convention against Torture (1984) both uphold the prohibition of torture or any form of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. These foundational documents are significant as they affirm the principle of honoring human dignity and safeguarding individuals from such mistreatment. Consequently, they establish a collective responsibility to alleviate pain and suffering while safeguarding human rights. Ensuring human rights, including access to pain-free treatment, is essential in healthcare and social justice initiatives.

These considerations are based on the concept that causing and managing pain might be regarded as a tool of power and injustice, meanwhile pain management is a basic and global human right.

According to the World Health Organization's estimation in 2012, approximately 5.5 billion people reside in countries where there is limited or no availability of controlled medicines and insufficient access to treatment for moderate to severe pain. Despite repeated reminders from the Commission on Narcotic Drugs to countries regarding their obligations, 83 percent of the global population lacks adequate access to treatment for moderate to severe pain. Millions of individuals, including approximately 5.5 million terminal cancer patients and 1 million end-stage HIV/AIDS patients, endure moderate to severe pain annually without access to proper treatment. (Human Rights Council 2013)

Slide 18: Pain communication: Doctor-patient interaction

Numerous experts have underscored the importance of effective communication between patients and clinicians in achieving successful pain management. However, research indicates that discussing pain can often be challenging, highlighting an urgent need for improvement. In addition to the vital role of communication in pain management, extensive research in health communication suggests that effective patient-clinician interaction across various aspects leads to direct, positive outcomes for patient care. These outcomes include heightened patient satisfaction, enhanced treatment adherence, and improved clinical outcomes. Adequate communication regarding pain can address both medical treatment and serve as a placebo effect that impacts pain intensity. Patients who leave a consultation feeling acknowledged and validated by their clinician may be more likely to follow the clinician's recommendations regarding non-pharmacological pain management techniques. This adherence, in turn, could lead to improved pain-related outcomes.

Since the experience of pain, as we have seen, is subjective, its measurement depends on the patient, and it is the doctor's responsibility to unconditionally accept it.

Slide 22:

Finally, as a form of provocation, I will present the thoughts of social critic Ivan Illich, who fundamentally questions and "overwrites" the place and significance of pain and pain relief in society.

Ivan Illich (1926–2002) was an Austrian Roman Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher, and social critic. In his critique, he highlighted the excessive focus of modern society on education and medical interventions. In his 1975 book "Medical Nemesis," he introduced the concept of medical harm to the sociology of medicine, arguing that industrialized society significantly impairs quality of life by overmedicalizing life, pathologizing normal conditions, creating false dependency, and limiting other, more healthful solutions.

„When cosmopolitan medical civilization colonizes any traditional culture, it transforms the experience of pain.(1) The same nervous stimulation that I shall call “pain sensation” will result in a distinct experience, depending not only on personality but also on culture. This experience, as distinct from the painful sensation, implies a uniquely human performance called suffering. (2) Medical civilization, however, tends to turn pain into a technical matter and thereby deprives suffering of its inherent personal meaning.(3) People unlearn the acceptance of suffering as an inevitable part of their conscious coping with reality and learn to interpret every ache as an indicator of their need for padding or pampering. Traditional cultures confront pain, impairment, and death by interpreting them as challenges soliciting a response from the individual under stress; medical civilization turns them into demands made by individuals on the economy, into problems that can be managed or produced out of existence.4”

On the last slide, we summarized how Ivan Illich thinks about pain in terms of independence, human competence, context, and responsibility. The table shows how he believes social existence colonizes the experience of pain.

Killing of Pain / Limits to Medicine

References:

Chen, L.-H.; Lo, W.-C.; Huang, H.-Y.; Wu, H.-M. A Lifelong Impact on Endometriosis: Pathophysiology and Pharmacological Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087503

Horne, A.W.; Saunders, P.T.K.; Abokhrais, I.M.; Hogg, L.; on behalf of theEndometriosis Priority Setting Partnership Steering Group. Top ten endometriosis research priorities in the UK and Ireland. Lancet 2017, 389, 2191–2192.

Kvaskoff, M.; Mu, F.; Terry, K.L.; Harris, H.R.; Poole, E.M.; Farland, L.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis: A high-risk population for major chronic diseases? Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 500–516.

Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256

UpToDate (2024) Endometriosis

Anand, Kanwaljeet JS, et al. "Historical roots of pain management in infants: A bibliometric analysis using reference publication year spectroscopy." Paediatric and Neonatal Pain 2.2 (2020): 22-32.

Baird and Sheffield (2016) The Relationship between Pain Beliefs and Physical and Mental Health Outcome Measures in Chronic Low Back Pain: Direct and Indirect Effects. Healthcare (Basel). 2016 Aug 19;4(3):58. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030058. PMID: 27548244; PMCID: PMC5041059.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5041059/

Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Jul;14(7):502-11. doi: 10.1038/nrn3516. Epub 2013 May 30. PMID: 23719569; PMCID: PMC4465351.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4465351/

De Sario, Gioacchino D., et al. "Using AI to Detect Pain through Facial Expressions: A Review." Bioengineering 10.5 (2023): 548.

Henry SG, Matthias MS. Patient-Clinician Communication About Pain: A Conceptual Model and Narrative Review. Pain Med. 2018 Nov 1;19(11):2154-2165. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny003. PMID: 29401356; PMCID: PMC6454797.

Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Apr 19;113(16):4296-301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516047113. Epub 2016 Apr 4. PMID: 27044069; PMCID: PMC4843483.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4843483/

Human Rights Council (2013) Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez

https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A.HRC.22.53_English.pdf

IASP: Pain in Women. https://www.iasp-pain.org/advocacy/global-year/pain-in-women/

IASP (2007) IASP declares the Global Year Against Pain in Women. https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/630641

Jensen, M. P. (2011). Hypnosis for chronic pain management: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

Prell T, Liebermann JD, Mendorf S, Lehmann T, Zipprich HM. Pain coping strategies and their association with quality of life in people with Parkinson's disease: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021 Nov 1;16(11):e0257966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257966. PMID: 34723975; PMCID: PMC8559924.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8559924/

Oláh, Mara (1997) Önéletrajz. Magánkiadás.

Trachel and Cascella (2019) Pain Theory

van Rysewyk, Simon, ed. Meanings of Pain: Volume 1. Springer Nature, 2016.

van Rysewyk, Simon, ed. Meanings of Pain: Volume 2: Common Types of Pain and Language. Springer Nature, 2019.

Zoffness, Rachel (2019) Think Pain Is Purely Medical? Think Again.Psychology Today (October 25, 2019) https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/pain-explained/201910/think-pain-is-purely-medical-think-again

Bushnell, M. C., Ceko, M., & Low, L. A. (2013). Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 14(7), 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3516

van Rysewyk, Simon, ed. Meanings of Pain: Volume 1. Springer Nature, 2016.

van Rysewyk, Simon, ed. Meanings of Pain: Volume 2: Common Types of Pain and Language. Springer Nature, 2019.

Pain Med. 2018 Nov; 19(11): 2154–2165.

Published online 2018 Feb 1. doi/ 10.1093/pm/pny003 Patient-Clinician Communication About Pain: A Conceptual Model and Narrative Review; Stephen G Henry, MD1 and Marianne S Matthias, PhD2,3,4,5

Oláh Mara: Önéletrajz, a szerző magánkiadása, ISBN 963-550-230-3, 28)

https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A.HRC.22.53_English.pdf

Trachsel, L. A., Munakomi, S., & Cascella, M. (2024). Pain Theory. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545194/

PinTheoryLindsay A. Trachsel; Sunil Munakomi; Marco Cascella.

Facial expression of pain

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a promising tool for automating and objectifying pain assessment through the identification of pain-related facial expressions.

source: Gioacchino et al: Using AI to Detect Pain through Facial Expressions: A Review (2023)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10215219/

Pain is an unpleasant subjective experience caused by actual or potential tissue damage associated with complex neurological and psychosocial components [1,2]. Self-reporting is the primary method of assessing pain, as it is highly individualized and dependent on the individual’s perception [3,4].

The medical literature provides several pain scoring systems for pain assessment, including the 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS), the numeric rating scale (NRS), and the color analog scale [5,6,7]. Studies have shown that the VAS is a highly reliable and valid measure of pain and is the most responsive to treatment effects based on substantial evidence [8].

Despite its value, the VAS is beset by several shortcomings. For instance, it is not feasible to employ it in situations where the individuals are either unconscious, cognitively impaired, or unable to articulate themselves verbally [9].

Observational scales have been developed and validated for use in different clinical settings and with specific patient populations to address patients’ inability to communicate their pain. These scales, such as the Behavioral Pain Scale, Nociception Coma Scale, and Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale [10,11,12], offer an alternative method for assessing pain but are limited by the observer’s previous training and ability to interpret the pain responses accurately.

Additionally, studies have found that observer biases can affect the results of these scales [13,14,15]. Therefore, there is a need for a genuinely objective pain assessment method that is also time-sensitive to detect changes in the patient’s pain experience.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to transform the healthcare system by making the analysis of facial expressions during pain more efficient and lessening the workload of human professionals. In particular, AI can automate feature extraction and perform repetitive and time-consuming tasks requiring much human effort by utilizing machine learning (ML) algorithms and data analysis techniques; this may result in better patient outcomes, better use of resources, and lower operating costs [16,17].

Erica Jacques: Pain Scales: Types of Scales and Using Them to Explain Pain (2023)

https://www.verywellhealth.com/pain-scales-assessment-tools-4020329

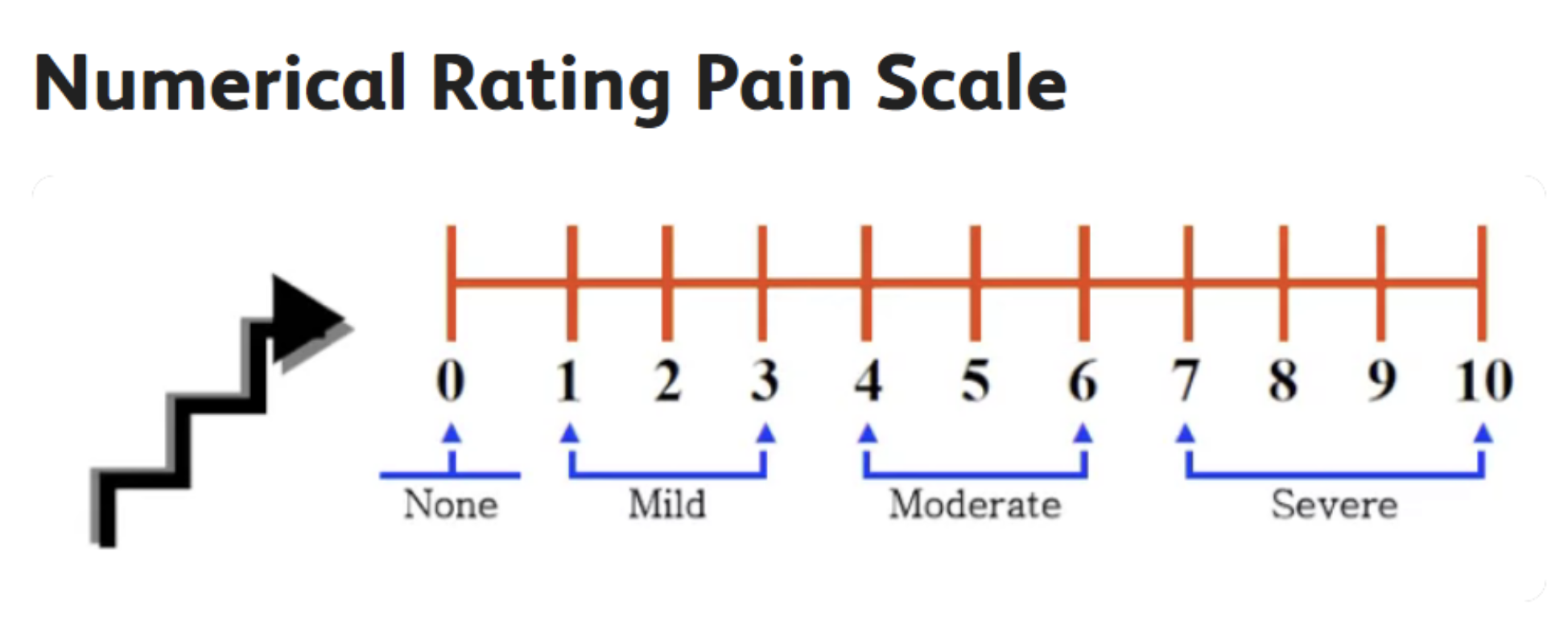

Numerical Rating Pain Scale

NIH / Warren Grant Magnusen Clinical Center

The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) is designed for anyone over age 9. It is one of the most commonly used pain scales in health care.

To use it, you just say the number that best matches the level of pain you are feeling; you can also place a mark on the scale itself.

Zero means you have no pain, while 10 represents the most intense pain possible.1

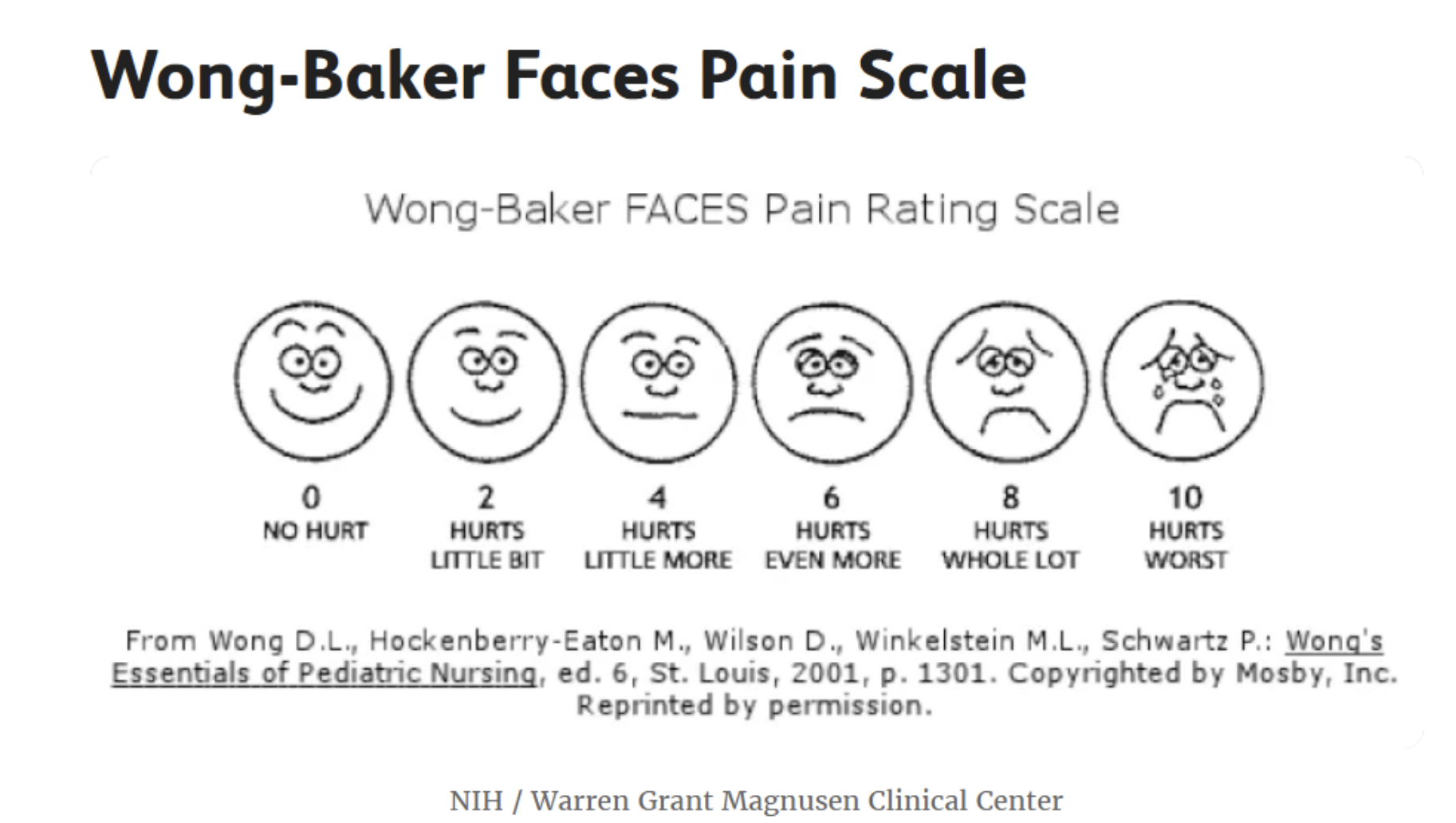

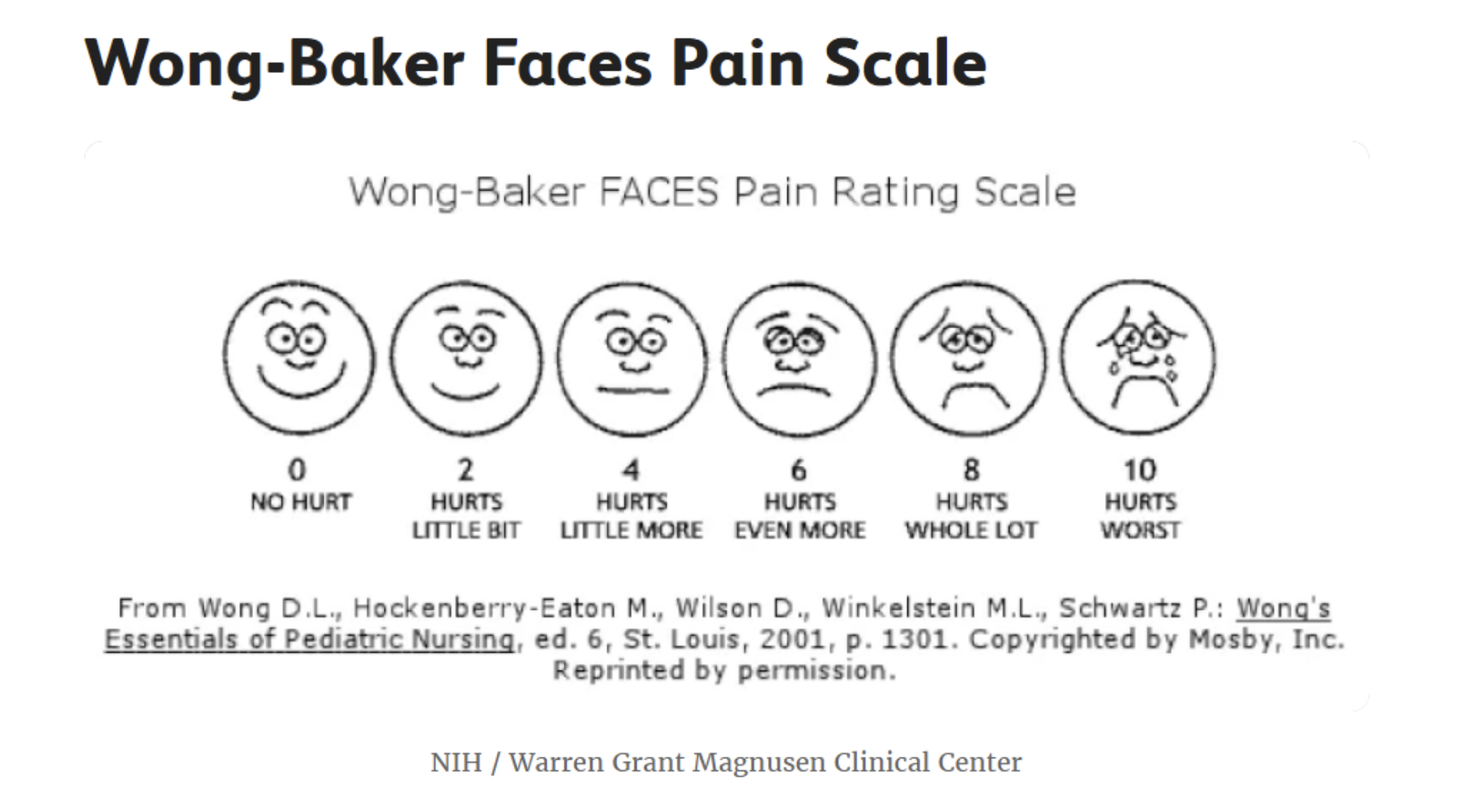

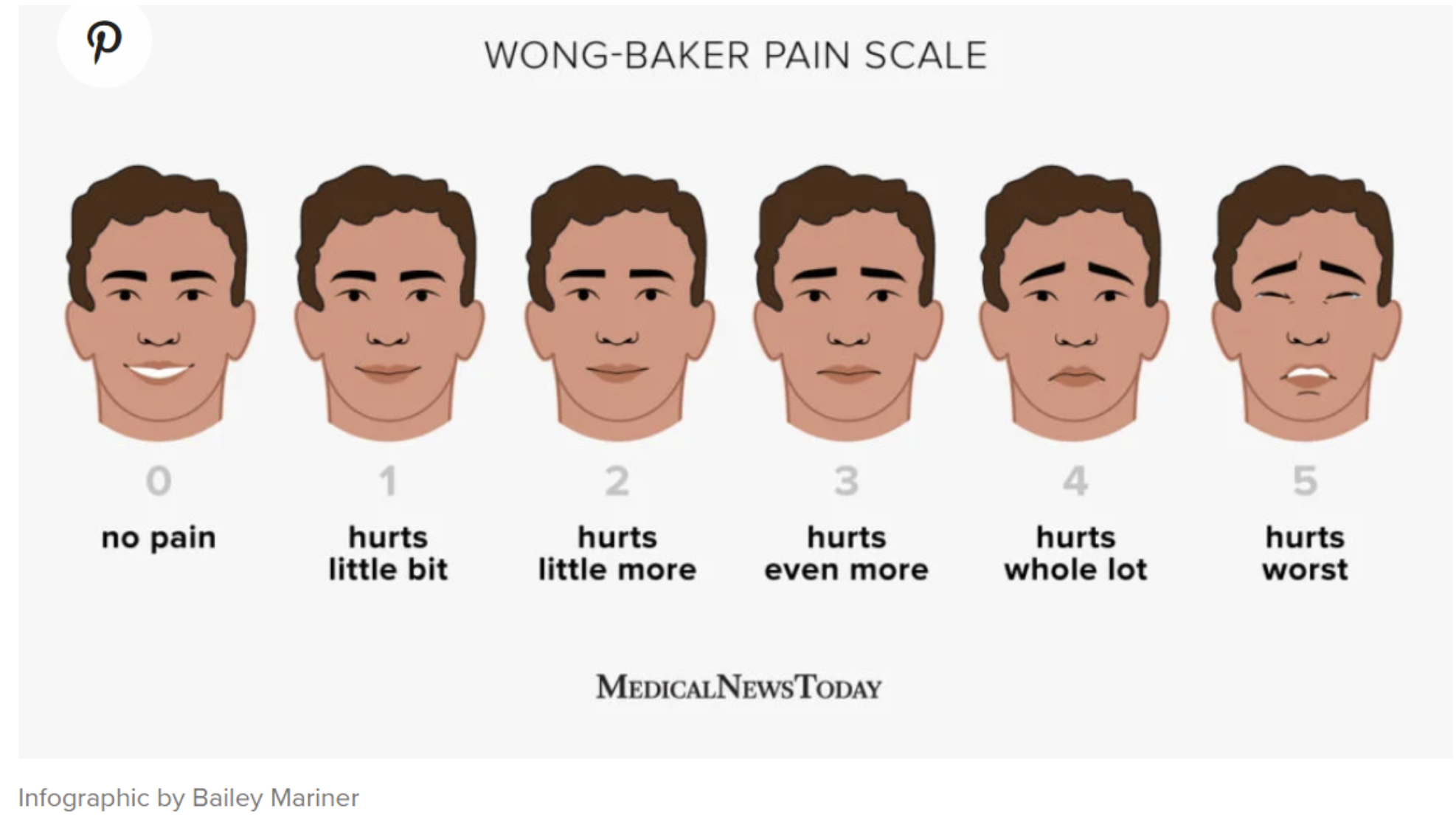

Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale

NIH / Warren Grant Magnusen Clinical Center

The Wong-Baker FACES Pain Scale combines pictures and numbers for pain ratings. It can be used in adults and children over age 3.

Six faces depict different expressions, ranging from happy to extremely upset. Each is assigned a numerical rating between 0 (smiling) and 10 (crying).2

To use it, you can point to the picture that best represents the degree and intensity of your pain.

Primary and Secondary Chronic Pain

FLACC Pain Scale

NIH / Warren Grant Magnusen Clinical Center

The FLACC Pain Scale is based on observations made by a healthcare provider. Originally created to evaluate young children, it can be used for anyone who cannot communicate.3

FLACC stands for:

Facial expression

Leg tension or relaxation

Activity (still or squirming with pain)

Crying

Consolability (whether you can be comforted)

Zero to two points are assigned for each of the five categories. Then the overall score is tallied. Scores are interpreted as follows:

0: Relaxed and comfortable

1 to 3: Mild discomfort

4 to 6: Moderate pain

7 to 10: Severe discomfort/pain

By recording the FLACC score on a regular basis, healthcare providers can gain some sense of whether someone's pain is increasing, decreasing, or staying the same.

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/wong-baker-pain-scale

https://www.britannica.com/science/pain/Alleviation-of-pain

(https://www.verywellhealth.com/pain-scales-assessment-tools-4020329). A fájdalom kifejezése információt ad az orvosnak, segítheti a beteg történetének és tapasztalatainak megértését, azok értő és támogató meghallgatása pedig segíti az orvos - beteg kacspolatot, a beteg tapasztaéatát és akár gyógyulását is.